Back Country Horsemen

A few days after getting Coquetta, my neighbor to the southeast,

Arlene Walsh, asked me to join the Back Country Horsemen of America

. This is a national organization devoted to keeping public lands

open to horseback riders. We figure horses should be a natural

part of the wilderness. After all, they originated here in the

Southwest. It was only 10,000 years ago that people hunted horses

to extinction. When the Spaniards arrived, their horses took

to the wild and thus, as far as I am concerned, righted a great

environmental wrong.

Our opponents are self-described environmentalists who want

to wipe out wild horses again. They don't want them in the wilderness,

not even as visitors, chaperoned by humans. They cloak their

hunger to extirpate horses with fancy environmentalist talk.

To fight these people, we need allies. We make them the hard

way by doing volunteer work on public lands. Our project for

the morning of May 31, 1992, was to make it easier for antelope

to get to a water hole on Bureau of Land Management (BLM) land.

Arlene wanted to make sure I hauled Coquetta to the day's work

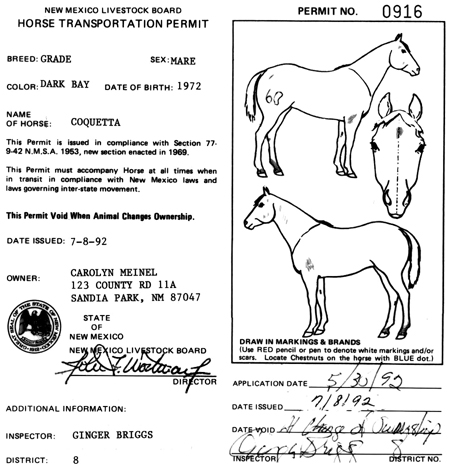

site without breaking the law. The authorities fight rustlers

by requiring hauling permits. Every now and then they stop a

vehicle that is hauling livestock and check to make certin everything

is in order.

Since I'd never seen news stories about rustlers, I figured

they were just being extra careful. Soon my opinion would change.

Early in the morning of May 30th, we met an officer of the

New Mexico Livestock Board at her place. I showed my sale agreement,

and got permit number 916.

Early the next morning, we all met at the junction of Interstate

40 and State Highway 6 to caravan deep into the backcountry.

We headed south, then west on a red dirt track. We angled deep

into a land of red and yellow sandstone mesas toped with black

volcanic rocks south of the Acoma Pueblo.

It was a dry spring. Our vehicles rattled over a washboard

road covered with red dust. We raised such a cloud of dust that

most of the convoy became blinded and took a wrong turn. Those

of us in the lead waited at a group of corrals and a water tank

until our leader retrieved the others. I let Coquetta out to

stretch her legs. She rolled in the dust and shook it off.

Our first task was to figure out how to get to the work site.

The concept was to get on our horses and head west. The reality

was a deep arroyo across our path. People rode north and south

trying to find a way to get through it. Everywhere, dense mesquite

and steep banks blocked the way.

After about ¾ hour all the folks that had gotten lost

in the dust arrived and saddled up, yet we still hadn't figured

out where to cross the arroyo.

What the heck. I gave Coquetta her head. She took off, dit-dit-dit-dit,

with her swift singlefoot gait, headed south about 100 yards,

pushed through some tamarisk bushes, and there was a well-worn

trail through the arroyo.

On the other side, Coquetta begged to get up and go like she'd

never begged before. A teenage boy on a mule cantered up to us.

"Let's run," he called.

I let Coquetta show me how fast she had to go to break into

a canter, then a gallop. After a run of a mile or so we came

to a Chevy ¾ ton pickup with a BLM logo, parked on the

other side of a barbed wire fence.

Why the heck, if a pickup could get to the work site, did

the rest of us have to come in on horseback across that arroyo?

The big deal was that the holder of the grazing rights, the Acoma

Pueblo, didn't care to have lots of random people driving around

their ranch. A strange truck would normally mean a cattle rustler

or poacher.

I walked Coquetta a bit to cool down, then unsaddled her and

wiped the sweat off. We tied her and the mule side by side. As

we walked over to meet the BLM men, I looked back. Coquetta and

the mule were making sweet sounds and nuzzling each other.

We soon found out another reason to ride to this site instead

of drive. The two BLM men had us get into their pickup and drove

us to the far end of the work area. The dirt track was so bad,

it felt like the truck had no shocks at all.

Our job, they explained, was to remove several hundred yards

worth of the bottom strand of barbed wire from the fence and

replace it with smooth wire. "Antelope don't jump fences,"

said one of the BLM men. "They crawl underneath. Along here

is where they crawl under to get to the water hole. We keep on

finding their babies here, dead from thirst. We figure they are

afraid to crawl under the barbed wire."

At the end of our day's work, once again Coquetta and the

mule begged to run. Because we would be trailering them right

away, we didn't let them go fast enough to work up a sweat. Even

so, again we left the rest of the work crew way behind.

I was beginning to suspect that my homely old mare was pretty

darn good.

Next chapter: Sandia's Foals --->>

Back to the Table of Contents for

Killer Buyer: True Adventures of a New Mexico Horse Dealer

Coquetta's hauling papers. The birthdate of 1972 was only

a guess. We later learned she was more like thirty at this time.